How Vulnerability + Curiosity Can Teach Us More About Each Other

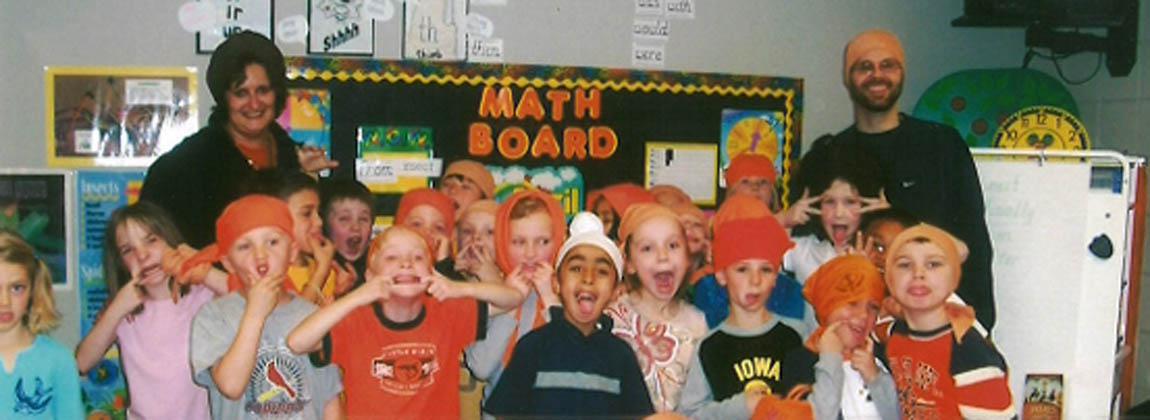

Header image: JJ shortly after a turban time session with his first-grade classmates.

My friend Karen recently asked for my take on the word “curiosity.” She belongs to an anti-racism committee at her Christian church, Plymouth Congregational.

Plymouth has been around for a long time. The only other church that has been around for almost as long is Corinthian Baptist Church. Both churches are only three miles away, but since the 150 years they have been established, neither church has made large-scale efforts to talk to each other. Karen had a hypothesis as to why: race. Plymouth’s congregation is predominantly white. Corinthian’s congregation is primarily Black. These racial and cultural differences affect how each community practices Christianity.

Bridge-Building Through Curiosity

Karen felt that these differences masked the similarities that bound both congregations together. She worked with her anti-racism committee to commit to a year of bridge-building with Corinthian Baptist Church. Karen called the project “Connecting with Curiosity.” In the spirit of bridge-building, Karen thought “curiosity” was the first place to start. But some members of her anti-racism committee disagreed. For them, “curiosity” was a bad word. When Karen told me this, at first, I was confused. Wasn’t “curiosity” a universally positive comment? Like “rainbow?” Or “vacation?”

According to a few of Karen’s committee members, curiosity is overly intellectual: it comes from the head, not the heart. Curiosity is the word used to describe a scientific researcher with a hypothesis who collects data to determine if this hypothesis is false. Interfaith allies are apparently not scientists.

“Is curiosity a bad word?” I asked myself this question as I sat in front of my keyboard, not yet ready to compose an email reply to Karen. Then, a memory caught me by surprise. A memory from my childhood. A memory from daycare.

Spoiler alert: I hated daycare.

I hated the food, especially “ants on a log.” Yes, the peanut-butter-coated celery sticks topped with raisins. My peanut allergy transformed this gourmet toddler treat into a nightmare. While my peers happily munched away, I sat at the peanut-free table with my untouched “raisins on a stick.”

But there was something, someone, I hated even more than this dreadful snack. Steven.

Steven was a little older than me, and he made it clear that he didn’t like me. He never smiled at me and cringed when I protested nap time. He scowled when I talked during reading time. But strangest of all, he shuddered at the sight of my patka. Because of my Sikh faith, I choose not to cut my hair. When I was five, my hair touched my lower back. A “patka” was the cloth I used to cover my hair at school.

One day, Steven approached me on the playground. He reached up from behind with deft hands and pulled my patka off my head. My long, black curls came tumbling down. Cackling, Steven sprinted off towards the blacktop as if his secret mission had gone as planned.

JJ, with his 4th grade best friend, now dawning larger turbans, before a Beatles Rock Band duel.

My ears rang. My cheeks burned. My jaws clenched. Without my patka on, I felt naked. No one at daycare had ever seen my hair before.

I looked up to see my teachers towering over me. The look of horror on their faces startled me more than Steven’s prank. It was an expression I had never seen my daycare teachers make — something between helplessness and panic. It felt like the ending from Humpty Dumpty where all the king’s horses and all the king’s men couldn’t put JJ’s hair back together again.

The daycare staff called a joint meeting with my and Steven’s parents. Steven’s mom apologetically explained that Steven had Autism, and part of his Autism manifested in severe rule-following. By wearing my patka to daycare, I was wearing a hat, which was breaking daycare law in Steven’s eyes.

Steven’s mom said she would talk to him about the incident on the playground, but she couldn’t promise us that it wouldn’t happen again. One of the daycare teachers then turned to my parents and asked, “Why is JJ’s hair so long?”

My father gave a brief synopsis of our Sikh faith and a core belief of our faith: that our hair is a sacred gift from God. After a momentary silence, there was a single follow-up question: “So…how do you tie it?”

My mom got up from her seat and demonstrated in live action. All the daycare staff huddled around her. If they had notepads, I swear they would have been furiously scribbling down what they saw, like medical students watching a skilled surgeon in the operating room. It all happened so quickly. My mom split my hair into three parts, formed a loose braid, twisted the braid into a top knot, tied my patka over my hair, and voila, Humpty Dumpty was back together again. Returning my hair to its original state, I suddenly felt more at ease and less naked.

Not long after my daycare days were over, my dad started coming to my homeroom classes at elementary school once a year for “Turban Time.” It would start with a trivia round on world religions, basic facts about Sikhism, and finally, the moment everyone seemed to be waiting for — turban-tying. The trivia got harder as the grade levels increased and the turbans grew bigger. By middle school, my classmates knew about Sikhism so well that when new students arrived, I wouldn’t need to explain my faith to them; my friends would do that for me.

I remember once, during a Turban Time session, a student raised their hand to ask my father a question about our faith, but the student started with, “Sorry…this is a stupid question…” My father quickly interjected, “There’s no such thing as a stupid question.” This small statement seemed to shoo away some invisible elephant in the room because a lot more hands suddenly shot into the air.

Curiosity can feel uncomfortable because before we can exercise curiosity, we must exercise another muscle that is painful to stretch: vulnerability. My experiences growing up as a Sikh in Iowa have taught me that there is an essential link between curiosity and openness. I am not sure my father knew it then, but he made a brilliant parenting move. It’s not like my father thought one day, “This kid will get asked many questions at school because of his appearance … I need to make sure he is comfortable being vulnerable.” But that is precisely how my parents raised me.

Papa introduced me to experiences I never knew I would need, from encouraging me to run for Vice President of my elementary school so that I could practice sharing my story in front of the entire student body to encouraging me to let my hair down for our school talent show and sing “Stayin’ Alive” so that students could see my long hair. This vulnerability to reveal myself and make myself and my faith legible in front of a large audience lies at the core of my being.

If I could talk with those daycare teachers today, I would tell them thank you. Thank you for being vulnerable. Thank you for being curious. Thank you for doing what great educators do best — learning from your students more than your students could ever learn from you. Beyond expressing gratitude, I would also humbly request that you add a sun butter substitute to your ants on a log; “ants in the sun” is simply more accommodating.

Greater Des Moines (DSM) welcomes diverse talent to the region. As one of the fastest growing business communities, inclusion and attracting diverse talent in the workplace is a key strategy of the Greater Des Moines Partnership. Inclusion Awards also recognize employers strengthening Diversity, Equity and Inclusion efforts in their organizations and are awarded during the annual Inclusion Summit.

Jeevanjot "JJ" Singh Kapur

JJ Kapur is a first-generation Sikh American and a proud Iowan. After graduating from Stanford University, he returned to his hometown of Des Moines as an AmeriCorps Lead for America Fellow. He serves with CultureALL, a nonprofit bringing Iowans together from diverse backgrounds to create a shared sense of community. At CultureALL, JJ’s building a human library across Iowa called Open Book. Open Book storytellers are Iowans from different cultures, religions and identities. They give “Readers” the chance to “check out” a “book” from our catalog, listen to a chapter from their life and have a conversation with the storyteller. JJ hopes readers walk away from an Open Book experience with a newfound appreciation for what happens when we choose not to “judge a book by its cover.”